I’ve been enjoying my experience watching the Calcutt Middle School as it looks to reimagine itself and I’m just one of many people who are excited about the possibilities.

Principal Milisauskas and the new outdoor lunch area

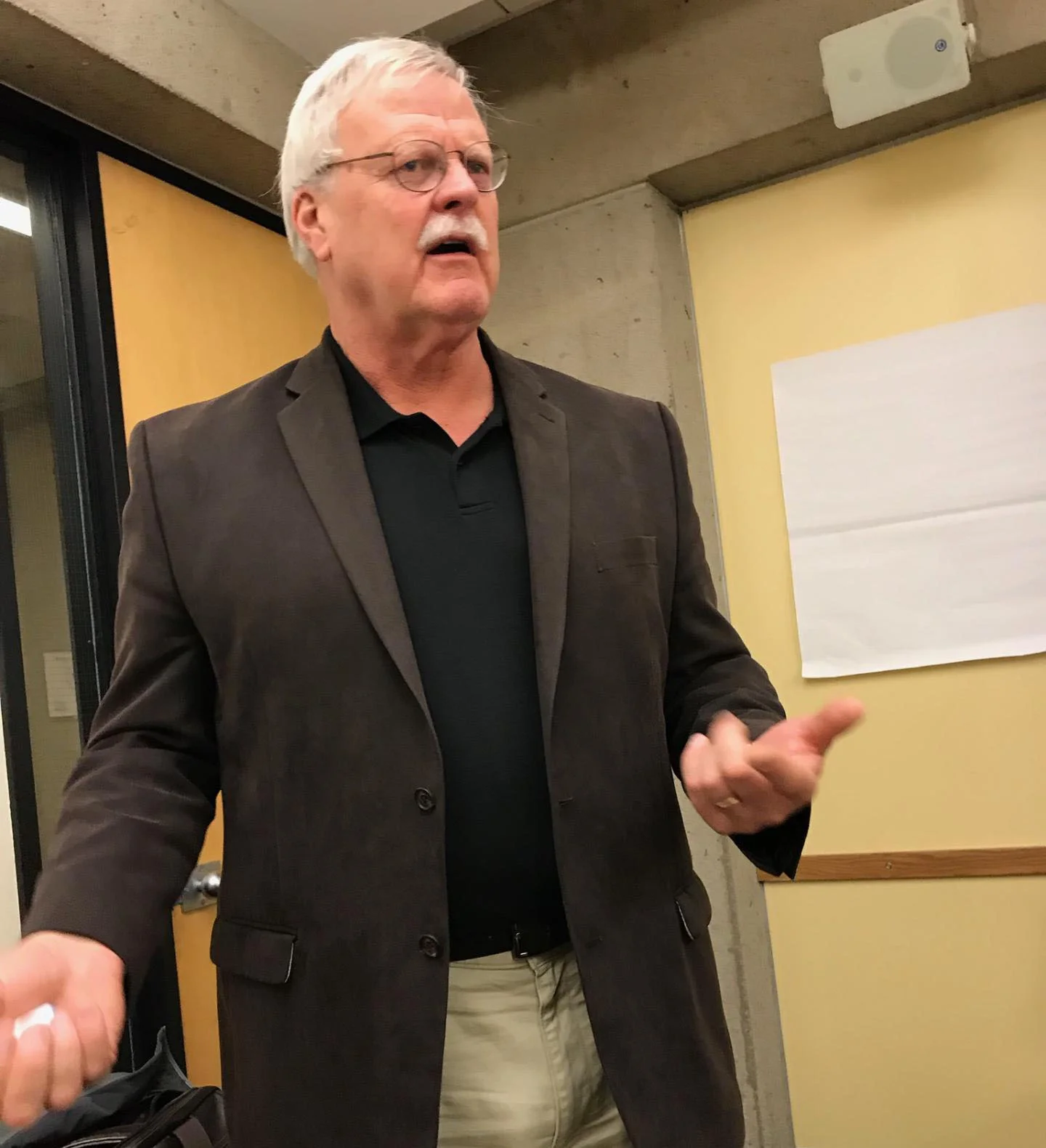

Located in Central Falls, Rhode Island, Calcutt has launched a voyage to become “the place to be” in the community. I really like that phrase from new Principal Tim Milisauskas. Its short and sweet but I hear it as a promise to the students and families.

Milisauskas brings a history of teaching in NYC’s progressive schools, a deep interest in inquiry learning and Reggio Emilia and strong expertise in instruction, having been a math coach before joining the ranks of principals. He’s excited to be in Central Falls and committed long-term to the growth of its students and its practitioners.

The Calcutt student body is a beautiful tapestry of languages and heritage, and as with most middle schools, the kids come in all sizes, shapes and flavors, so to speak. To greet them at the front door each morning is inspiring, with their diversity and enthusiasm on full display. Sports, support for new arrivals from other nations, and a strong team that manages after-school activities and tutoring are becoming more central elements of the student experience and fund-raising has begun to add more to the menu, including efforts led by the students themselves. And the faculty have dug into some key aspects of a strategy for raising achievement, which I’ll get to.

But how are they doing with that mission of becoming “the place to be”? One data point from the winter months, a time that can be challenging as cold sets in and days get shorter, was when an estimated 300 families attended this year’s Family Game Night. The evening included all manner of board games, popcorn, pizza and drinks. Even Santa Claus was available for gift requests, small talk and photos with each and every family.

Thinking back, Assistant Principal Katie Gomes felt especially good about the event, recounting inside stories of families enjoying each other’s company, including some recently reunited, eating together and playing board games. Many students whose parents could not attend, came with friends or other relatives, lending the hoped for family feel. Especially cool was that people were persistent in asking when the next such event would be. While in the past, similar attempts to engage caregivers often resulted in low turnout, the energy this time around was positive and appreciative. Close to three hundred families! Seems to me that one milestone was achieved in identifying the school and its staff as people who want to take good care of this rising generation of Americans.

I find being around Central Falls to be relaxing and comfortable. These working people are clearly hustling but most take time to greet you, and unlike our home base in the Boston area, they routinely let your car enter at busy intersections. There are some great Latino restaurants and bodegas as well as good burgers. But it also can be said that Central Falls is a community that, to Milisauskas’ point, needs more positive places, given its chronic high unemployment and an ever-growing influx of people looking for a good place to set down roots. Historically, levels of school achievement have reflected low income, lack of familiarity with English, and frequent relocations experienced by many families. (Here is where I have to point out that, since the 1930’s beginnings of achievement testing, the one relentless scientific correlation regarding test performance is with income --one’s ZIP code. If your family has the means, you will be likely be well supported in learning and achieve at higher levels. There are occasional short-lived exceptions, but it’s a given that students in privileged, economically well-off communities outscore others on tests.)

Santa at a Family Game Night

A centerpiece of the Central Falls School District’s improvement efforts is a refreshed and revitalized Calcutt Middle School, including some structural changes and an investment in collaboration and professional learning for staff. I’m pleased to be supporting the Calcutt administration and its newly minted Principal Leadership Team (PLT) as they take stock and plan next chapters. I’m also working on behavioral climate with the school’s Restorative Team and ERC will be assisting with the design of an Inquiry and Innovation Academy, similar to work we have done elsewhere, building on an inquiry-approach to learning and breaking some of the bonds that have limited STEM results in other places.

Students enjoy an “luncheon out with reservations, menus and reading” with teachers Justyna Barlow and Laticia Biggerstaff.

Calcutt’s Principal Leadership Team examines data together

The new Calcutt Principal Leadership Team has worked closely with Milisauskas to employ a Design Studio approach that ERC has used successfully elsewhere to take stock of current conditions -challenges and assets from user perspectives (students, staff, families), identify key levers, research effective solutions and pose potential modifications and pilots for the faculty and staff. The work requires careful analysis and consensus, and of course time, which schools never seem to have enough of. But Special Educator and teachers’ association representative Danielle Laferriere says the school is moving in the right direction after an extended era of challenges, “I think our staff sees us leaving ‘survival mode’ behind. There’s lots of work ahead of us, not just improving academics but coming together as a faculty, supporting each other and growing together, but I’m optimistic”. In addition, a new school-based communications team (SBT) helps to monitor progress and engage the community for input and dissemination.

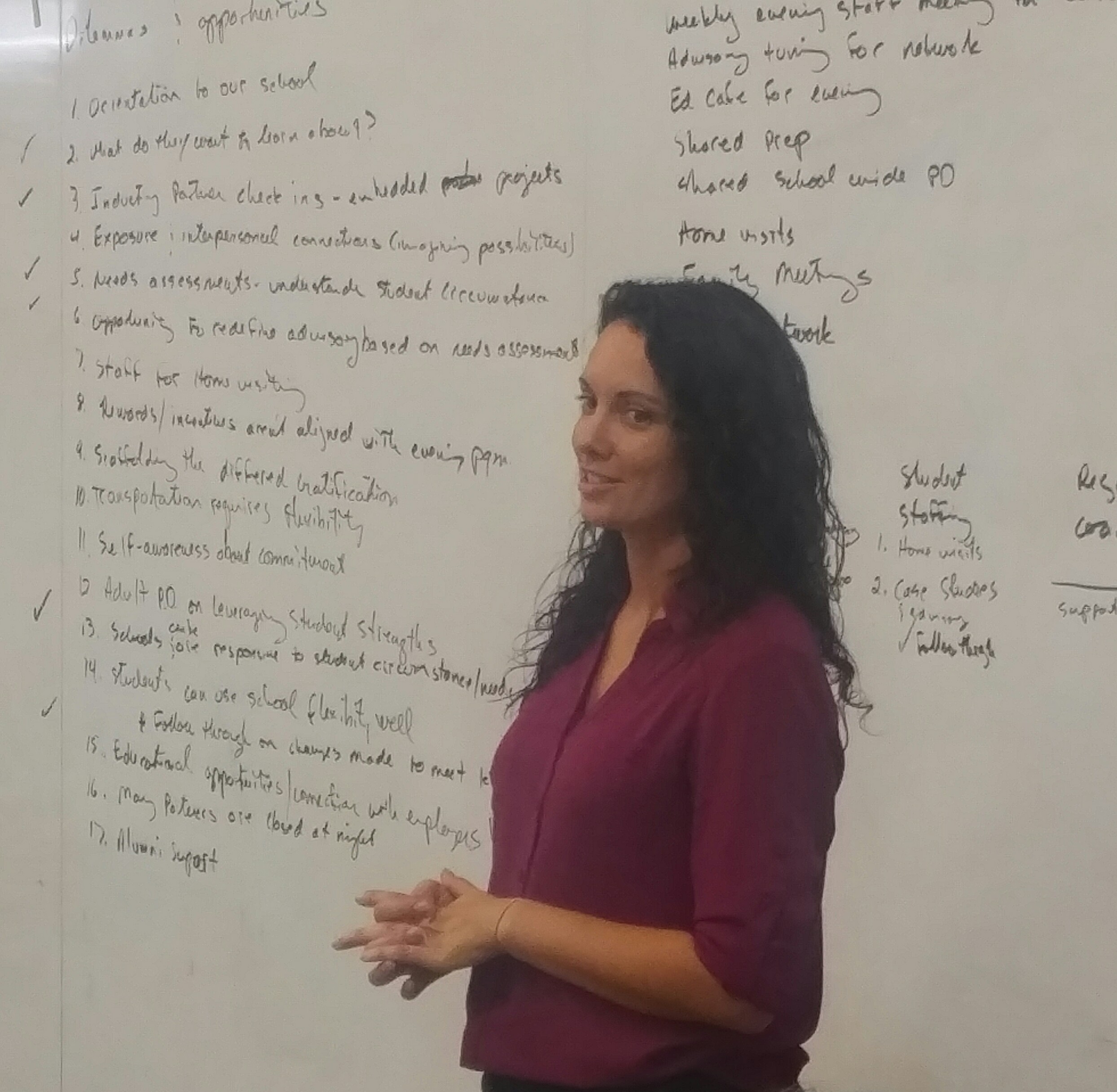

To guide the Calcutt Design Studio work, Milisauskas posed the driving question, what are the elements of an optimal middle years learning environment? To gain thought partnership and perspective in pursuing that redesign question, members of administration and the PLT have been on visits to other middle schools in the northeast region. Milisauskas has been steely-eyed on the benefits of such visits. Historically, funders and intermediaries have built on visits to other schools, hoping for adults’ conversion to new ideas, replacing old pictures of school with new, and relying on a small group of travelers returning to oversee the dramatic conversion of the sending schools. Being the former leader of a school that hosted hundreds of visits a year, I would say the return on investment was, and remains, remarkably low. Milisauskas however has applied ERC’s School Visit Guide and expanded notions of visiting other schools as a learning adventure, with an accent on metabolizing the adult experiences and take-aways for smart use back at Calcutt. Link to guide here. The PLT members visited East Side Middle and High School and Lenox Academy in New York City where they were impressed by the students’ ability to pursue their own learning with strong academic habits and language.

As a veteran of many similar “make-over” efforts I’m curious as to how a school re-design quest can reflect newly abundant data about key elements: mental health, exercise and mindfulness, reading science, and positive youth development (PYD), among others. I’m also focused with Principal Milisauskas on the importance of adult mindset regarding organizational behaviors such as intense teaming and collaboration and working with students with starkly different language and cultural backgrounds. As I’m fond of noting in presentations, improvement in schools with histories of low-achievement has been shown to depend a great deal on educator mindset --belief in one’s colleagues, in their students and in the mission--- and on skilled leadership, rather than on more instructional, “technical fixes”, especially in the early stages. Those can come later, built upon a strong set of agreements among elements of the school community.

And then, of course, we’re asking what lore is there to draw on regarding the past century’s history of middle years education? Middle schools have often been a neglected or murky entity since their advent in the 1920’s as “’junior’ high schools”. In 1910, only one out of every ten students were finishing high school. The middle years experience was perceived to be at fault, but that failure was attributed to differing rationales -a rigid, narrow emphasis on academics; a curriculum insufficient in its organization and rigor to prepare students for the upper grades; a missed opportunity for steering numbers of students into vocations; or the neglect of a growing understanding of pre-adult psychology. Some believed junior high schools should be places to prepare students for the academic rigors of high school; while others considered young adolescents to be a group at risk requiring, above all, support and understanding. Tyack and Cuban, in their stellar history of American public education, Tinkering Toward Utopia, describe it this way:

“The very ambiguity of purpose and comprehensiveness of these aims made the junior high school idea a reform to conjure with during successive decades of the 20th century. Although the junior high school did not become distinctively different from the high school and came to be seen as a rather troubled part of the American educational system, it did sponsor changes that became hybridized in various ways.”

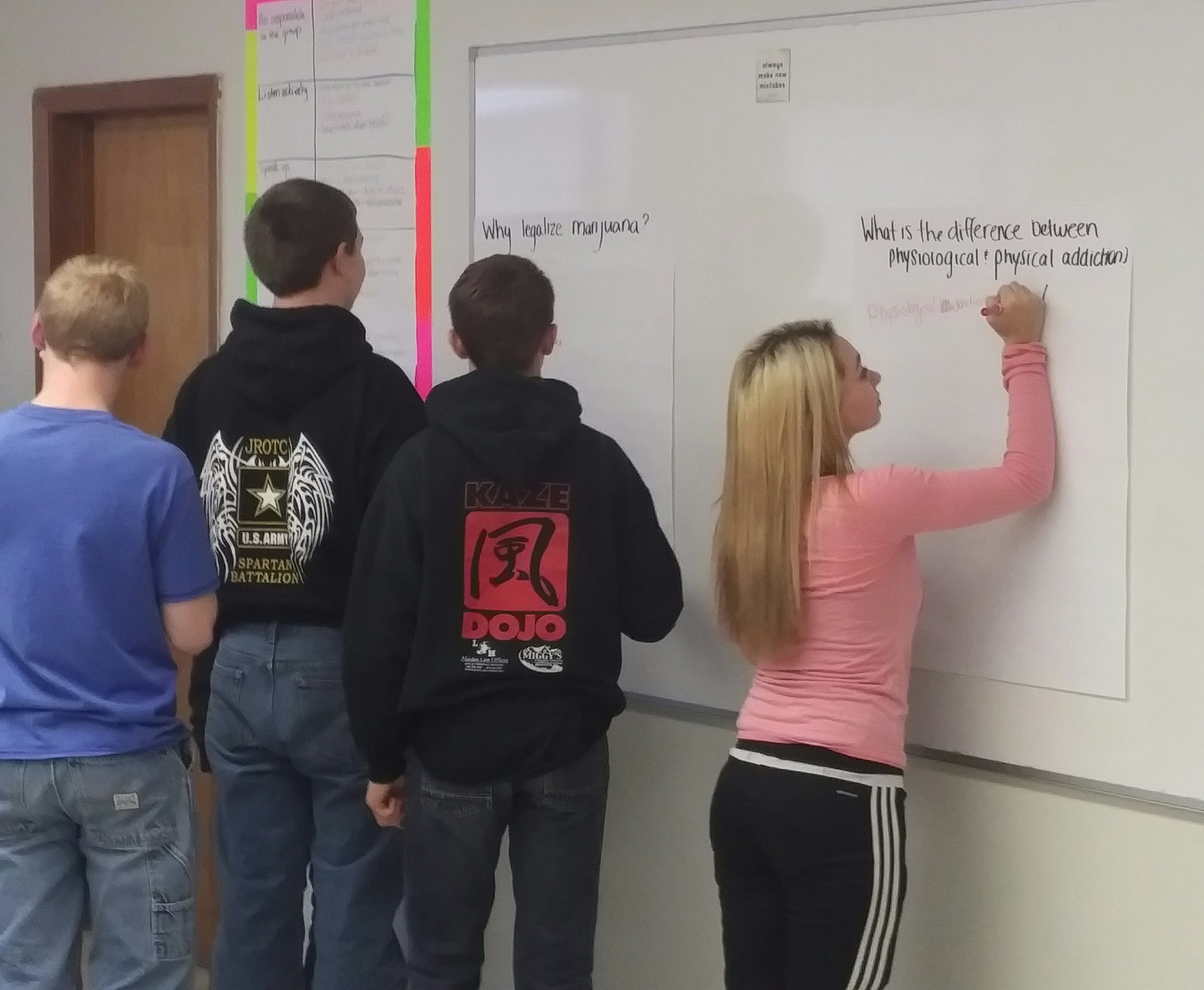

Calcutt STEAM workshop

To Tyack and Cuban’s point, varying visions of effective middle school organization still compete today. The stark differences among students in their size and physicality, social and emotional growth and development and location on the puberty continuum, as well as disparities in developmental reading abilities and academic skills have made it challenging to sustain supportive middle years environments that consistently address such a chasm of needs. Some states and districts, with good intentions, have even divided academic services and support in the middle years into two “levels” -grades 5/6 and grades 7/8, but this often means unhelpfully dichotomized programming, schedules, achievement targets and educator certification requirements. Such delineations too often fail to account for the afore-mentioned developmental and academic differences, can limit creativity and flexibility in teaching and learning, and constrain vertical collaboration among staff --the law of unintended consequences at work.

Calcutt’s Restorative Team reviews data

Back at the school, Noel Grant, who coordinates Calcutt climate with the skilled “Restorative” team, has also noted progress, especially among 8th graders. His notion is that although challenges remain, the investment in strategies that build a healthy climate is beginning to show, and as younger students climb through the grades, they will be bringing positive habits and relationships with them, paving the way for higher achievement.

“Calcutt Reads” -students read before gym class

Two central initiatives were inaugurated this year – “Calcutt Reads”, an effort to make reading central to students’ lives by making it central to conversations in the school, as well as a central focus on vocabulary. Teachers committed to these two vital efforts with vitality, and now, along with candid color pictures of students and teachers that have sprung up in formerly barren hallways, signs indicating what books staff are reading and “key words of the week” are everywhere. Students now answer, most without hesitation, questions about what they’re reading as well as new words they’ve learned and practiced. Again, this in a school with many students new to the language and culture of literacy, so these are purposeful and promising efforts.

WhatIf Math

As one more sign of the school’s renaissance, May visitors to the school were Arthur Bardige and Peter Mili, Co-Founders of WhatIf Math, a powerful new approach to making math problem solving more of a concrete, consistent, and understandable process across the discipline. With the goal of helping students become more able problem-solvers, WhatIf Math is finding a foothold among schools looking for an inquiry-based approach to learning math for the digital age. Milisauskas, who was a math instructional coach in a prior life, is excited about their approach to preparing students for high school and far beyond and is in negotiations with Bardige and Mili about concrete next steps over the summer.

As a finale to a special new year, the Calcutt staff offered a “Lock-In”, a supervised and fun-filled overnight for students at the school. Adults were there in force, some for shifts and others for the whole night! The social media post below offers a glimpse of the fun.

Calcutt “Lock-In’s” social media post

As an onlooker, as well as a veteran coach of many similar efforts, I’m impressed by the commitment and understanding of school change leadership that Milisauskas brings to the work --he’s a key acquisition for Central Falls- and by the vitality and increasing buy-in of many educators at Calcutt. Key faculty are stepping up –some with special activities in the classroom, others participating in school leadership, others communicating with families. For many, this is what they’ve been waiting for.

All in all, Calcutt is a very different school from the one I visited only a year ago. It’s making parents, students and staff proud to be part of it. It’s a school becoming “the place to be”.

Larry Myatt

Co-Founder