It certainly feels like a moment.

We’re talking about race, pretty much everywhere. 70% of us now think Black Lives Matter. We’re asking questions about policing, about healthcare, about our commitments to each other. People are in the streets, peacefully but forcefully. Heroes are passing away while others step forward.

The moment feels new, and volatile. Some students have drifted away from school. Online offerings are often thin, and relationships with adults have frayed in the vacuum. Perhaps more than anyone, young people are organizing and asking for change. Students of color especially are speaking about their experiences with racism in their schools, saying things that we might have heard before with any serious listening.

These dynamics are bringing big educational issues to the surface. We’ve heard the question, is this the beginning of the end for standards and testing? At the community level people are asking, is it time for an overhaul of the ways our schools operate? With COVID fraying so much of what we once thought of as “school”, can we rely on the educational establishment to respond to the moment?

ERC is deeply engaged in a number of these cross community dialogues. To guide us, we asked five people with deep knowledge of schools, their inner workings, their shortcomings and their successes to comment on the moment -five leaders with their hands on the pulse in different places and at different junctures. Here’s what they told us:

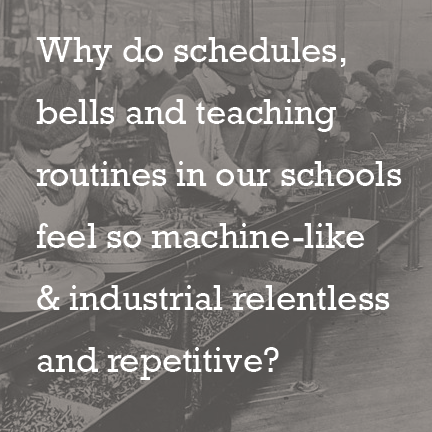

For so many, their schools pre-COVID were not working well to begin with. Now the pandemic has highlighted huge gaps in how we serve young people, especially along the lines of race and class. The way we’ve organized our schools, and continue to organize them, has been outdated for some time. There’s little argument about that. The content we’ve chosen is socially constructed, and we’ve married outcomes to certain standards, and now we’re finding out those ideas have put us in a serious bind.

In many locations parents and caregivers see schools as places to be avoided. How do I not have to send my children to that school, or that school? We’ve extended the free market notion to schools, so if you have the means, you can escape the predicament by virtue of where you live or the school you can afford for your child. Testing is for those with no alternative, and we know that many if not most of the problematic places are those that serve poor, black, and brown children.

We’re kind of throwing out some of the rules these days in other areas. Re-thinking how we want to conduct our business. Now COVID has rocked our sense of the traditional school day, relationships among adults and young people, the idea of grades, even where and how we can be in contact with young people, Again, things in our schools pre-COVID were not working well to begin with. Like many others, whose voices are increasing, I’m not sure the educational authorities can or will respond to this moment, and we may not see a moment like this again for a long while, if at all.

There is a lot of energy in the air. I hear students, families, teachers looking for something different. People want to be heard and we need to hear them. I think an important step would be the creation of more community-based schools, schools where partners provide the services we know students often lack, and where families and residents have a large measure of control over how they operate, how they are supported and how their success is measured. And not to spend years talking about that idea. It’s going to be hard for some people to wait with a hand out for the educational establishment to provide the opportunities and permissions. It’s not unreasonable for people to want new and better schools for their children now, not down the road.

George Floyd and Breonna Taylor's deaths sparked a national uprising. Schools and districts, like other institutions are on their heels. They are reacting by getting "equity" training for their faculties, trying to provide racially sensitive curriculum and consider teaching in culturally sensitive ways. All good, but not getting at the real problem we face—much of what we do, much of our system is based on a potent but unexplored premise --that poor kids of color are problems. And, that somehow their communities are unworthy. The solutions we create are based in "fixing" the problem.

The real question we should be asking is, how can schools help make our communities healthier and more prosperous? Real and enduring equity will not happen until the communities where young people live are valued and educators see their job as to employ the resources and programming of the school to make that happen. We should be talking to people in the community and asking, "how would you know if the school in your neighborhood was making this community a better place to live?"

Racism is kicking our collective ass right now and we're not going to deal with it until we start to reframe and ask new questions. I'm fond of quoting Einstein, "you cannot solve a problem within the same consciousness that created it." Forget standards, testing and the damn performance gap. Focusing on that has gotten us nowhere. It's the wrong frame, and it’s not big enough for the unjust world that we have created and are handing to the next generation.

One evening, I was in an adult religion class meant for parents to refresh their faith while their children were preparing for Confirmation. There was a guest, a Jesuit priest, who told us that the church had it all wrong when they talked about the idea of confession. He told us, "you shouldn't ask for forgiveness for the bad things you’ve done. Instead, you should ask for forgiveness for the good things you didn't have the courage to do." I mention this because I don't think the people in the education sector are really able to take a hard look at the last two decades and the damage we have done. Let's admit that we don't have the answers, the forces are outside of our control and we need to start thinking much differently about the role of school. It's time to ask what it would take for schools to make our communities more just and better places to live, which is much more important than improving some outdated notion of school performance that was intended to oppress the kids who go there.

We face huge challenges in education related to inequality and traditional approaches to the way we organize schools and serve young people. Now is the time to devise new strategies to respond to the needs of kids and society. Universities can play a role in developing these ideas in partnership with practitioners. Having spent 30 years in academia and working closely with schools throughout the U.S, my goal as Dean at Rossier is to have it serve as a thought partner with teachers, policy makers and educational leaders on how to address the major challenges facing education in this new moment.

My hope is that this predicament and our responses can move standards in a different direction. Instead of using standards to direct schools on what to teach, we should think of standards as a way to ensure quality in learning opportunities so that all kids have access to a high-quality education regardless of where they live or go to school. Approaching standards in this way would be more like the way we conceive of standards for airports. Regardless of size or location, all airports must conform to certain safety standards. Similarly, regardless of where a school is located, all schools should provide students with an education that makes it possible for them to participate fully in society.

I am concerned because most of the focus related to the reopening of schools is focused on the logistics of keeping them safe from the virus. It’s understandable and obviously important, but it’s not sufficient. Beyond health-related strategies, I think the most important thing schools can do now is to ensure that the online learning they make available to kids is excellent and engaging. As we are seeing and hearing, if what we provide is not meaningful and interesting, many kids will tune out. Sticking with what we’ve always done will not suffice. I don’t hear about enough schools working on how to create learning opportunities for young people that tap into their curiosity and motivate them to learn.

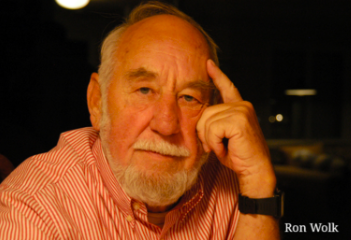

Well, I wish I could be more tuned in to the life of schools and school people. I miss the conversations, I miss the Coalition (of Essential Schools), and the progressive people and ideas. I was lucky. I feel like I was present at a time when there was a lot of hope, a feeling that we could make a difference, that our commitment to a democratic education had places to land and to shape the work. When we were in our 30’s, if we wanted to be good educators, we could feel a certain spirit of possibilities.

Thinking back to some of the things we’ve done over the last two decades, in New York City, and nationally, the bureaucratic approach, thinking that a technocratic approach could fix things, and structured to minimize the influence and control of people closer to the students has, again, gone nowhere. And with testing, if you have people feeling ashamed of their scores, or doubting their children and communities, no one will make a fuss about schools not being democratic.

Of course, schools have to manage the health threat from the pandemic, but beyond that I see quite a lack of imagination. I’m surprised that there isn’t more talk about schools and how to re-shape them for learning, and for democracy. I saw a nice piece by Marion Brady, who I’m delighted is still at it. And you’re (ERC) still at it. And Pedro is still at it, and others, thankfully. We have no idea of course, what will happen in the 2020’s. In the 50’s we had no idea about the 60’s, and in the 80’s we knew nothing about life in the 90’s. But I don’t hear that much that’s interesting, to me.

The common good seems up for grabs right now. There is, no doubt, a certain restlessness in the air. It could be that something could come of that. If we still take democracy, the common good, “we the people”, as well as Black Lives, seriously there is a path forward. Demand a nation-wide discussion, a version of which takes place in every community’s public school on how we define democracy? Do we see democracy as a fundamental public purpose of education? Do we persist in raising our future “citizens” in what is a thoroughly undemocratic institution? With those questions, we could start such public discourse anywhere and everywhere. Let all join in.

Our thinking about post-COVID schools and schooling does not seem, to me, to be up to the demands of our time. The health concerns are great, yes, but I think there is a danger of being too focused on regaining old ideas and feelings of “school” as we knew it. And not focused enough on engaging young people in more authentic learning that extends beyond “school”, and even enlarging our ideas of what schools are for.

In some places, people are beginning to ask, are we seeing the unraveling of standards and testing? And, should we be? And I think the answer to both is yes. So much of what we’ve heard in the discussion of schooling over the past two decades has lacked a real sense of purpose, the result of which is perhaps best summed up by Einstein: “Education is that which I learned after all that I had been taught was forgotten”.

How big is our opportunity? As big as we want to make it, I think. There are certainly bigger questions to be asked than most of what I’m hearing: Are we ready for new kinds of schools right now? Should we be abandoning a fair share of what we currently do? This is a golden moment to support true voice and ownership from students, families and their communities. Schools need to be much more in service to their communities and as a result, this is the time to redesign learning and “school” as we currently know and experience it. I want to be a part of that work.

There you have it. Calls for action, for hard questions. Calls for communities to elevate the dialogue, and take the lead in making decisions about their schools.

We hope you will pass on their commentary and the ideas they espouse. Let’s stir up some good trouble together. A gracious thanks to our respondents. Thanks for their time and energy and yours as well.

If you’re inspired, take a journey to a school that’s different.

educationresourcesconsortium.org/reimagining-school

Please feel free to contact us! Stay healthy. Help others do the same.

Larry Myatt

Co-Founder