Where did the furor over teacher evaluation go? Just five years ago it was the behemoth that overtook American schools. The only conversation in town. Now? It’s hardly on the radar screen. What happened?

In 2001 Congress passed the “No Child Left Behind Act” with great fanfare and desperation. Politicians and policy makers believed that something radical had to be done to improve our schools and save our economy from the ravages of a poorly educated workforce. When President Bush signed this act into law in early 2002 it became the most sweeping educational reform initiative since the days of President Lyndon Johnson. The law had bi-partisan support and promised radical changes in student performance and school accountability. But, by 2010 when student’s cognitive abilities, as measured by performance on paper and pencil standardized tests, proved to be resistant to improvement a “blame game” began in Washington and elsewhere.

At that juncture, the popular rationale regarding flat student performance became, “it must be the teacher’s fault”, and its cousin, “why aren’t those principals evaluating out those bad teachers?” Our national fixation on testing was supplemented by a new fixation on teacher evaluation and administrative management. Those of us in the business –teachers, building and district administrators, and trainers- remember the flurry well.

The Federal government dangled multi-million dollar carrots in front of states and school districts to encourage an overhaul of their teacher evaluation systems. The common wisdom was that if we could tie teacher evaluation, student performance, and merit pay together we would finally have the formula for success. Many of our nation’s most prominent funders and businesspeople jumped on the bandwagon. Private money followed public funds in support of this notion. Huge amounts were spent on the development of “new and improved evaluation programs” and hundreds of millions more on professional development to train educators on how these new teacher accountability systems were going to work.

Virtually all other professional development activities ground to a halt as training of administrators and teachers to use new evaluation instruments and management techniques swamped all other needs and plans. It was the singular focus of states, districts, schools and educational professionals for three years. Surely, this was going to do the trick! Finally our public schools were going to produce higher performing students.

So, what has all of this spending and fixation on accountability accomplished? As the studies and evidence roll in, not a great deal.

Let’s take a broader look. School districts have struggled with teacher evaluation for years, making limited progress in developing systems that actually result in instructional improvement and increased student learning. State Departments of Education have regularly developed new models of teacher evaluation only to replace them every few years, but not, as I see, it, for rational and helpful reasons. In some states, teacher unions have collaborated with their Departments of Education on new evaluation models, again, only to retreat from them within a few years.

The way evaluations play out in far too many schools and districts is that an evaluator, whose real expertise has become the area of administrative management, data management and reporting, or student affairs, announces a date at which time she/he will come to observe a teacher at work with the class, usually for all or a good chunk of a class period. Depending on the labor agreements, the teacher may or may not have submitted a plan of what will occur in the class. This “formal observation” is usually supplemented by a few more “informal”, i.e. un-announced visits, that are shorter in duration, and which may or may not provide the opportunity for more data gathering on the teacher’s performance.

What it can feel like at the school level is inauthentic and inadequate, at best, and bad opera at its worst --a pretend panorama of the teacher’s daily routines and practices, mired in forms, dates for discussions about the findings, replies, claims and counter-claims, within which the essence of teacher performance and support thereof, diminishes substantially as the days go by. From the teacher standpoint, the process provides little insight into the real dilemmas of teaching, and little by way of getting at the nuanced formulas for sustaining growth and energetic teaching and learning in demanding settings, made even more stressful by the layers of testing and test prep.

To address these issues, the federal government used legislation, its bully pulpit and boatloads of cash to encourage “teacher accountability”. Most recently, the computer billionaire and amateur education policy wonk, Bill Gates seems to have become the most recent to fail at the teacher evaluation game. After an expenditure of more than 180 million dollars in Gates Foundation and other funds, and an estimated 50 million dollar per year cost to implement and maintain the initiative, The Washington Post recently headlined, “Another Gates-funded education reform project, starting with mountains of cash and sky-high promises, is crashing to Earth”. That project in Hillsborough, Florida Public Schools was one of many throughout our country that focused on teacher evaluation as the path to improved student performance and better schools. (https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/answer-sheet/wp/2015/11/03/bill-gates-spent-a-fortune-to-build-it-now-a-florida-school-system-is-getting-rid-of-it/ )

I don’t want to demean philanthropy in education. We need all the help we can get (if its spent in the right places and the right ways). I just want to highlight that when a government or groups of well-intentioned individuals make knee-jerk, simplistic reactions to highly- complicated problems like the factors that will improve student learning, those initiatives are likely to fail.

It wasn’t that long ago that the big idea about how best to bring about better student achievement was to get away from compensation systems that reward teachers for years of service and academic credentials earned, and instead implement merit pay evaluation systems that would reward educators based on the performance of their students. Unfortunately, scholars have found little or no evidence to suggest that merit pay has worked anywhere to improve student or teacher performance. No one talks about that idea much anymore. We’ve also learned that our national testing and school choice initiatives don’t sustain school improvement either.

We’ve even tried to use public humiliation as a way to improve teacher performance. At least two of our nation’s largest school systems (Los Angeles and New York) and the media that served those metropolitan areas thought that publishing a ranking of teachers by their composite evaluation scores, politely called teacher data reports in NY, might do the trick. As scholar and researcher Linda Darling-Hammond noted in a Phi Delta Kappan article, http://edsource.org/2012/pioneered-in-california-publishing-teacher-effectiveness-rankings-draws-more-criticism/6732 ) “a teacher’s effectiveness is determined by numerous school and non-school factors that a ‘value-added’ analysis typically doesn’t or can’t take into account. These might include variables such as the impact of peer culture, students’ prior teachers and schools, summer learning loss, access to tutors, and even the nature of the tests used to measure achievement.”

So, back to teacher evaluation. Those initiatives that were spawned a few years ago have focused on the development of complex educator evaluation systems, relying on explicitly-written teacher performance rubrics. These rubrics employ intricately-crafted instructional elements describing all possible teaching behaviors arrayed on a rating grid, similar to the old-fashioned teacher checklist evaluations, now on steroids. Where those old checklists simply referred to broad categories of instructional competence (e.g. classroom management, questioning techniques, use of higher order thinking skills, etc.) the new rubrics are intended to be both comprehensive and explicit in determining the “evidence” that will suggest a particular type of instructional strategy is “exemplary”, “proficient” or “needs improvement” or “unsatisfactory” (See, http://www.doe.mass.edu/edeval/model/ for a sample of a model of the rubric used for teacher evaluation in Massachusetts).

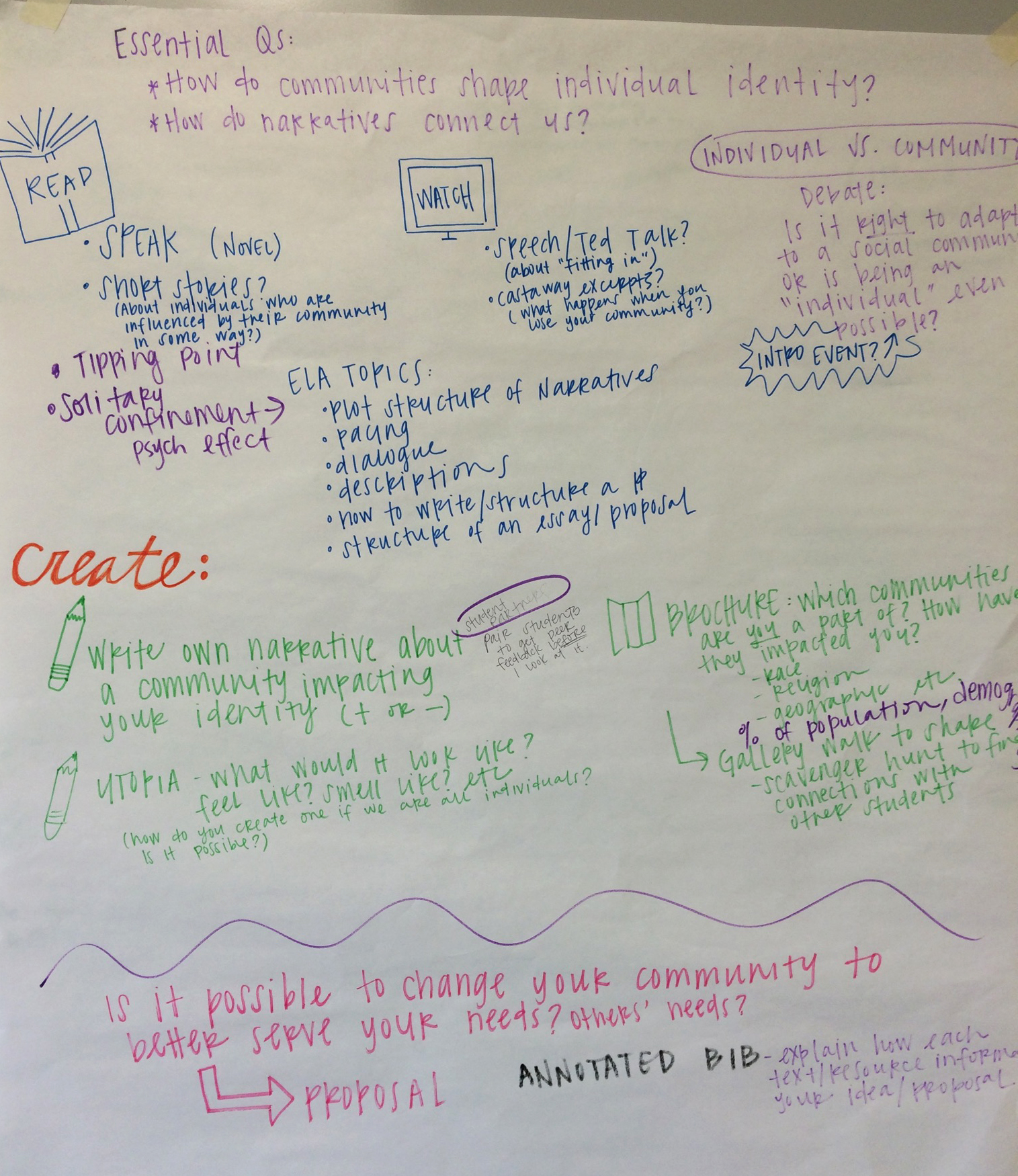

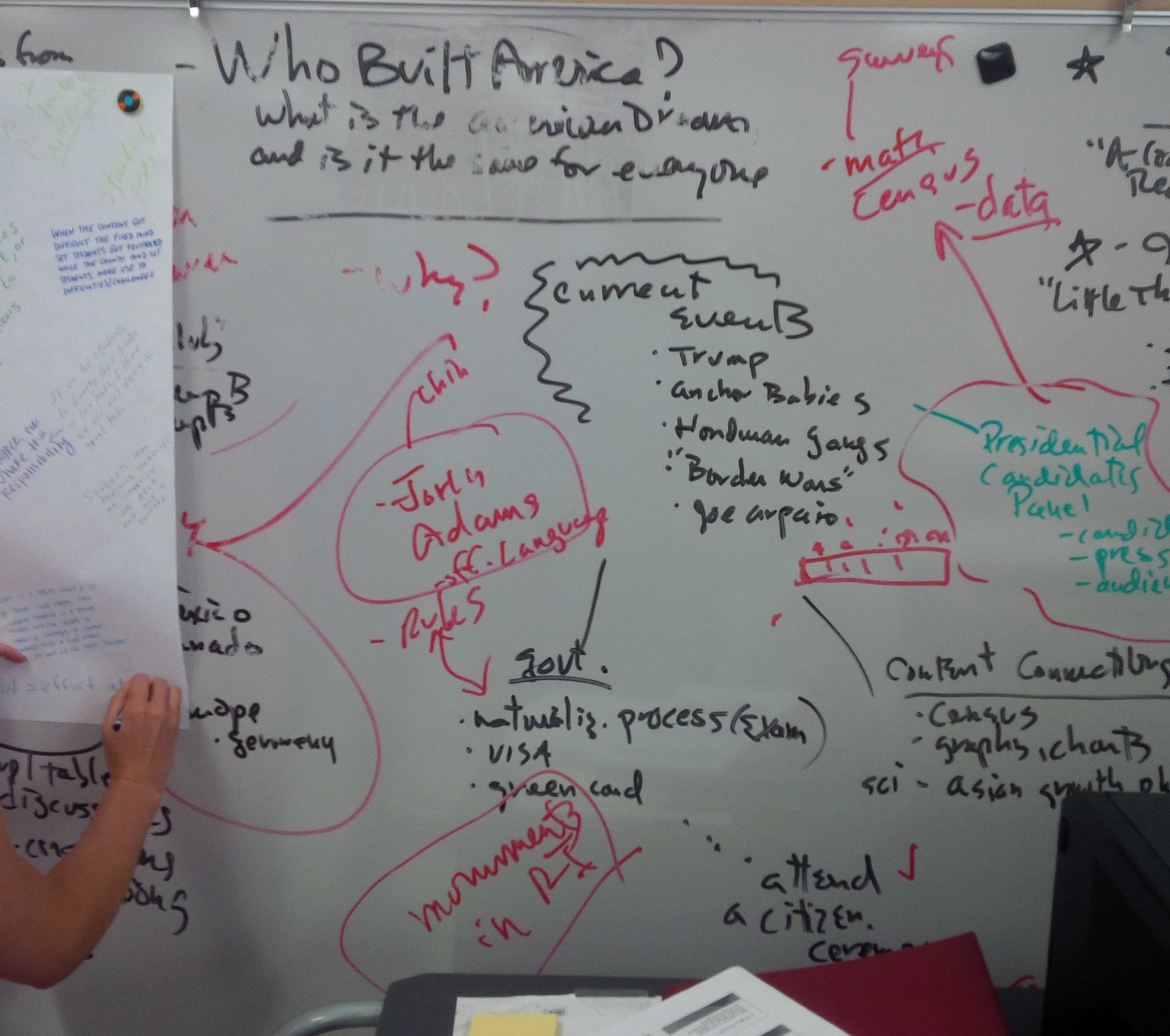

This type of educator evaluation system alleges that it draws upon the “science of teaching” to help inform and modernize efforts around instructional improvement. However, of significant note, the rubric model itself was originally designed (see Charlotte Danielson) to foster the professional development of teachers and instructional improvement in a collegial environment, not to “judge” or “rate” a teacher as “competent” or “incompetent” for the purposes of hiring, firing, retention or promotion. And as my ERC colleague, Larry Myatt often says, the effectiveness of what teachers do in the classroom can more easily be understood and examined if we watch the students, not the minutiae of teacher behavior. The idea of teachers-as-sole-and-dominant-actors is part of a century-old model –focused on a culture of teaching. What we need now is to understand the creation of a culture of learning and how the teacher’s role must change.

So, back to my initial question --why is getting teacher evaluation right so difficult and elusive? Why have so many different initiatives failed to achieve their desired result? I believe that it’s because we begin the conversations with the wrong question. If we start with questions about judging teachers and their teaching, we’re already on an impossible path. We need to re-frame, and to ask ourselves, what it is that will lead us on the path to the best teacher growth and improvement? And how does that contribute to the best kinds of student learning? What conditions and practices will result in the instructional excellence that we all desire for our kids?

Here’s a short list of things I think we should give a sustained try:

-Beginning teachers should be apprenticed for a complete school year to a master teacher in a co-teaching scenario (not as an understudy) for at least half of each school day. This would include collaborating with other teachers in the school and district.

-Compensate all master teachers at a higher level than their colleagues, but do not select them on the basis of seniority, but as a result of thoughtful process involving administrative, peer and student feedback.

-Master teachers should be part of the school’s leadership team.

-Schools must judiciously hire corollary staff to free teachers from operational duties that distract them from their essential function.

-School districts must support and engage administrators to differentiate instructional leadership from operational functions. Principals who spend their time on bus schedules, budgets and bullies will never have adequate time to devote to developing and supporting master teachers around issues of instructional excellence. Districts can and should hire sufficient staff that doesn’t need advanced degrees, licensure, and big salaries to perform routine, non-academic tasks.

-Summers should include at least 2-4 weeks of pertinent, differentiated professional growth activities for teachers and districts should put to rest the one-size-fits-all teacher PD that changes focus and content each year based on the flimsy trends we’ve named above -or that emanates from what the district currently thinks all teachers need.

-School leaders should be observing teachers at least one hour per week per teacher in all phases of their work (classrooms, student conferences, team meetings, etc.). No system of professional growth can work when someone is observed only a few times per year

-Administrators should engage with teachers and content areas to determine the kinds of routines, support, critique and provocation that are needed this year in this school.

-Require teachers to solicit and use student and parent feedback on a regular basis, as part of a broader conversation about how learning is taking place.

-Take a page from the world of art, design and architecture and develop faculty cultures where critique and feedback are positive, frequent and earnestly solicited, not seen as negative and unwelcome. This is the instructional leader’s real work,

-Provide every first and second-year school leader with an external coach. (See coaching new leaders:

http://www.educationresourcesconsortium.org/news/2014/12/9/new-leader-support?rq=new%20leader%20support )

Strong support for and evaluation of teaching is possible. But it’s going to take an investment in helping schools become alive and responsive again. Policy-makers need to get out of the way if they can’t do better than what they’ve shown us for the past 10 years. And framing the issue as the need to support for learning and those responsible for learning is critical, as is involving all parties in a conversation about the changes we need to make in our schools on behalf of children and families.

Wayne Ogden is co-founder of ERC, and a former teacher, principal and superintendent. He specializes in coaching school leaders and was a contributing author to The Skillful Leader, a handbook for administrators in supporting improved teaching. To see his piece titled, "The Six Myths of Coaching New School Leaders" go here.